Kantha

Introduction : Origin

The oldest forms of embroidery originating from India, Kantha embroidery's antiquity is attested by its origins, which can be traced back to the pre-Vedic age, circa 1500 BCE. Kantha embroidery has its genesis in the rural hinterlands of Bengal, specifically in the districts of Murshidabad, Birbhum and Nadia. The craft's evolution is deeply rooted in the traditional Bengali practice of repurposing and reassembling old garments to create new ones, a testament to the resourcefulness and thriftiness of rural Bengali communities. Over time, this pragmatic technique underwent a transformative metamorphosis, blossoming into an intricate and exquisite art form that showcases the ingenuity and aesthetic sensibilities of Bengali artisan.

The revitalization of Kantha embroidery was momentarily stymied by the tumultuous events of the Partition of India in 1947, which was further complicated by the subsequent tensions between India and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Nevertheless, the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 served as a catalyst for Kantha's remarkable resurgence, as it emerged as a highly coveted and esteemed craft. The etymological origins of the term "Kantha" remain shrouded in ambiguity, but a prevailing theory posits a connection to the Sanskrit word "Kathaa" which literally denotes rags. This linguistic association underscores the humble genesis of Kantha embroidery, which has evolved from a pragmatic technique for repurposing discarded garments into a revered and intricate art form.

The Evolution of Visual Expression Principles in Kantha Embroidery

Throughout the ages, kantha embroidery has undergone a remarkable transformation, adapting to various purposes and cultural influences. This traditional craft has evolved from its humble beginnings as a simple wrapper for personal items, such as arshilota (make-up case), bostani (clothes wrapper) and galicha (rug), to become a sophisticated art form.

Initially, kantha embroidery was characterised by a limited colour palette, dominated by red, black, and blue hues. However, contemporary kantha has expanded to showcase a vibrant spectrum of colours, incorporating primarily running stitch, alongside occasional blanket and chain stitches. The design process involves tracing patterns onto layered fabric, securing them with basting stitches, and embellishing them with vibrant threads. The strategic use of yarn stitches fills voids, producing a textured appearance that adds depth and visual interest to the fabric.

Traditional kanthas often featured central motifs, such as the Sun or lotus, which symbolised spiritual and cultural themes. However, the range of designs was vast, encompassing folklore characters, natural elements and everyday objects, influenced by both Indian culture and colonial interactions. The introduction of silken threads and maritime motifs by Portuguese traders, for instance, had a profound impact on the evolution of kantha embroidery.

Kantha frequently embodied familial aspirations, symbolising events from weddings to fertility, and served practical purposes during monsoon and winter seasons. More intricate pieces were cherished as wedding dowries, crafted by mothers and grandmothers who infused their hopes and family narratives into each stitch. Each kantha piece was distinct, reflecting the artisan's creativity, technique and colour choices, rooted in community tradition rather than royal patronage. Notably, while many Indian crafts waned under British colonialism in the 18th and 19th centuries, kantha persisted among rural women, who continued to practise and innovate this traditional craft. This resilience is a testament to the enduring significance of kantha embroidery as a symbol of cultural heritage, community, and artistic expression.

The Kantha Stitch: A Celebration of Ancestral Wisdom, CreativeSpirit, Methodologies and Identity.

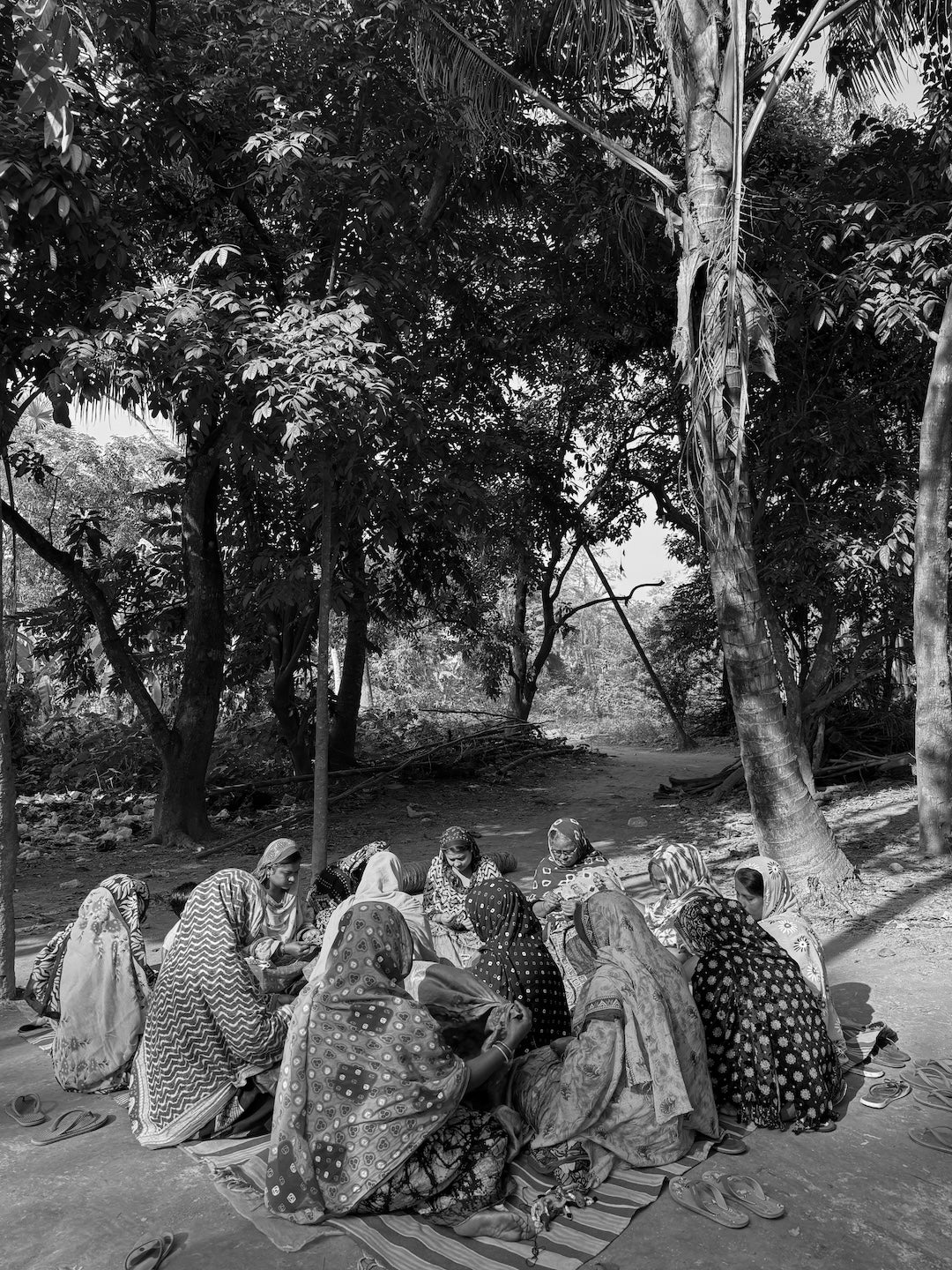

Historically, the kantha stitch was an integral part of domestic life in Bengal, woven into the daily routines of women as they managed their households, cared for their families and tended to their livestock. This traditional craft, primarily practised by women of diverse ages, involved the ingenious repurposing of worn-out garments, layering them with simple yet elegant running stitches and utilising threads salvaged from the edges of old sarees to craft functional items such as quilts, bed covers, and other domestic textiles.

The resultant fabric typically exhibited a distinctive, slightly crinkled texture due to the numerous stitching lines, with the original kantha being double- sided, showcasing identical designs on both faces. This craft not only exemplified the resourceful upcycling of textiles but also served as a medium for women to express their creativity, with nearly every woman in a village engaging in this practice for her home.

Furthermore, the kantha stitch often functioned as a narrative tapestry, chronicling the life experiences, myths and legends of the embroiderers. The designs frequently featured intricate religious themes and mythological scenes in Hindu households, while Muslim households leaned towards Islamic and Persian aesthetics, incorporating geometric and floral patterns. This rich cultural heritage is a testament to the enduring significance of the kantha stitch as a symbol of tradition, community and artistic expression.

The Taxonomy of Kantha Embroidery: A Classification Based on Stitch Variations

Kantha embroidery can be systematically categorised based on the type of stitch employed, revealing a rich diversity of techniques and regional variations. The earliest and most traditional form of kantha is the running kantha, characterised by a straightforward running stitch. This foundational style can be further subdivided into two distinct categories: nakshi kantha, which incorporates figurative motifs and narrative elements and par tola kantha, which features geometric patterns.

Another variant, Lik or Anarasi (pineapple) kantha, is prevalent in the Chapai, Nawabgonj and Jessore regions of northern Bangladesh, showcasing numerous adaptations and innovations. Lohori kantha, also known as 'wave' kantha, is favoured in Rajshahi, with its forms categorised into three distinct types: soja (straight), kautar khupi (triangular), and borfi (diamond).

Sujni kantha, exclusive to the Rajshahi area, is distinguished by its flowing floral and vine motifs, and is also practised in Bihar. Lastly, cross-stitch or carpet kantha was introduced during British colonial rule in India, representing a significant departure from traditional kantha techniques.

The advent of cross-stitch or carpet kantha during the British colonial era in India constitutes a paradigmatic shift in the traditional kantha repertoire, exemplifying the complex dynamics of cultural exchange, appropriation, and hybridization that characterised this period of colonial encounter.

The Contemporary Paradigm of Kantha Embroidery: Navigating the Intersection of Tradition and Commercialization :

The venerable craft of kantha embroidery has undergone a huge transformation, evolving from a personal and domestic pursuit to a commercialised industry. A notable corollary of this shift is the abandonment of repurposed fabric in favour of newly acquired materials, such as cotton and silk, which has significantly altered the craft's traditional practices and applications.

Furthermore, the demographic profile of embroiderers has undergone a significant metamorphosis, with kanthas now predominantly crafted by women from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, whereas previously they were created across various social and economic strata. This shift has raised important questions about the impact of commercialization on traditional crafts and the agency of artisans in navigating these changes.

While the personal use of kanthas persists, the majority are now produced by artisans seeking to earn a livelihood. This commercial approach often results in the creation of context-free pieces tailored to distant markets, thereby limiting the artisans' expressive potential and creative agency. However, commercialization can also foster a contemporary aesthetic, enhance the livelihoods and skills of artisans, and promote cultural sustainability, particularly when artisans receive fair compensation for their labour and are empowered to exercise creative control over their work.

Ultimately, the contemporary paradigm of kantha embroidery presents a complex and multifaceted narrative, one that underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of the intersections between tradition, commercialization and cultural sustainability.